In recent months, some have asked why Bermuda needs Marine Protected Areas. Many will know that Bermuda’s ocean, used for marine tourism, transport, fishing, and recreational activities, is already very active. However, the growing interest in ocean-based renewable energy, marine cultural preservation and aquaculture will make it even busier. Marine spatial planning aims to balance all these varied uses. In the middle of all these activities, it is also necessary to protect maritime heritage and include some areas for nature, too. Hence the need for Marine Protected Areas or MPAs.

MPAs serve to protect the various habitats essential for all marine life. Protecting a portion of each different type of habitat, from the shoreline to the deep ocean, gives each species at every level of the food chain a safe place to live and grow. These areas form a network of ecosystems that acts like an insurance policy, supporting biodiversity and providing flexibility to adapt to changing conditions.

These principles, and the science behind them, were endorsed at the recent United Nations Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity when 190 countries pledged to work towards protecting 30% of all marine and terrestrial habitats worldwide.

While this target may be high for a small area used as intensively as Bermuda’s marine space, following international best practices as best we can is important.

MPAs also protect areas that various species depend on to complete certain life cycle stages, often referred to as Essential Fish Habitat. We have seen in Bermuda how prohibiting fishing at the Red hind and Black rockfish spawning grounds gradually allowed the populations of these species to recover over time. At the moment, though, there are no specific regulations to protect the habitat at these sites to ensure they can continue to fulfil their essential function. On the other hand, the living mangroves, seagrasses and inshore corals that form important nursery habitats have some legal protections, but there is no broader protection for any particular areas.

For any of these areas to effectively fulfil their potential, excluding all activities that would damage the habitat or remove any marine life is essential.

Over time, as the number of fish and other marine life increase inside MPAs, they will contribute to the populations outside of the MPA borders, firstly because there will be more individuals spawning but also, more directly, through the outwards migration of adults. In this way, MPAs can replenish fished populations, increasing catches. Some recent examples of this effect include spiny lobsters in California and Yellowfin tuna off Hawaii.

MPAs are also used to protect maritime heritage assets such as shipwrecks. Bermuda has a unique area of shipwrecks that span the history of navigation of the Atlantic. It is not only a Bermuda cultural treasure it is a global heritage asset. We must protect this at the highest level. Measures designed to protect natural habitats and the associated marine life also serve to preserve historical artefacts. Indeed, many of Bermuda’s existing MPAs are centred on shipwrecks.

Unfortunately, although there are many reasons to establish a network of MPAs, the debate is often limited to fisheries and how the creation of MPAs can help or harm various fishing activities. Commercial fishermen often question why they must bear the cost of being unable to fish in a particular area and if this cost outweighs the potential benefits of MPAs.

Fisheries catch data are a useful indication of the status of fish populations. Still, independent surveys provide a broader perspective on a more comprehensive range of species and may highlight important areas more precisely than catch reports. These two approaches complement each other; therefore, both types of data were used to help develop the current Draft of the Marine Spatial Plan for Bermuda.

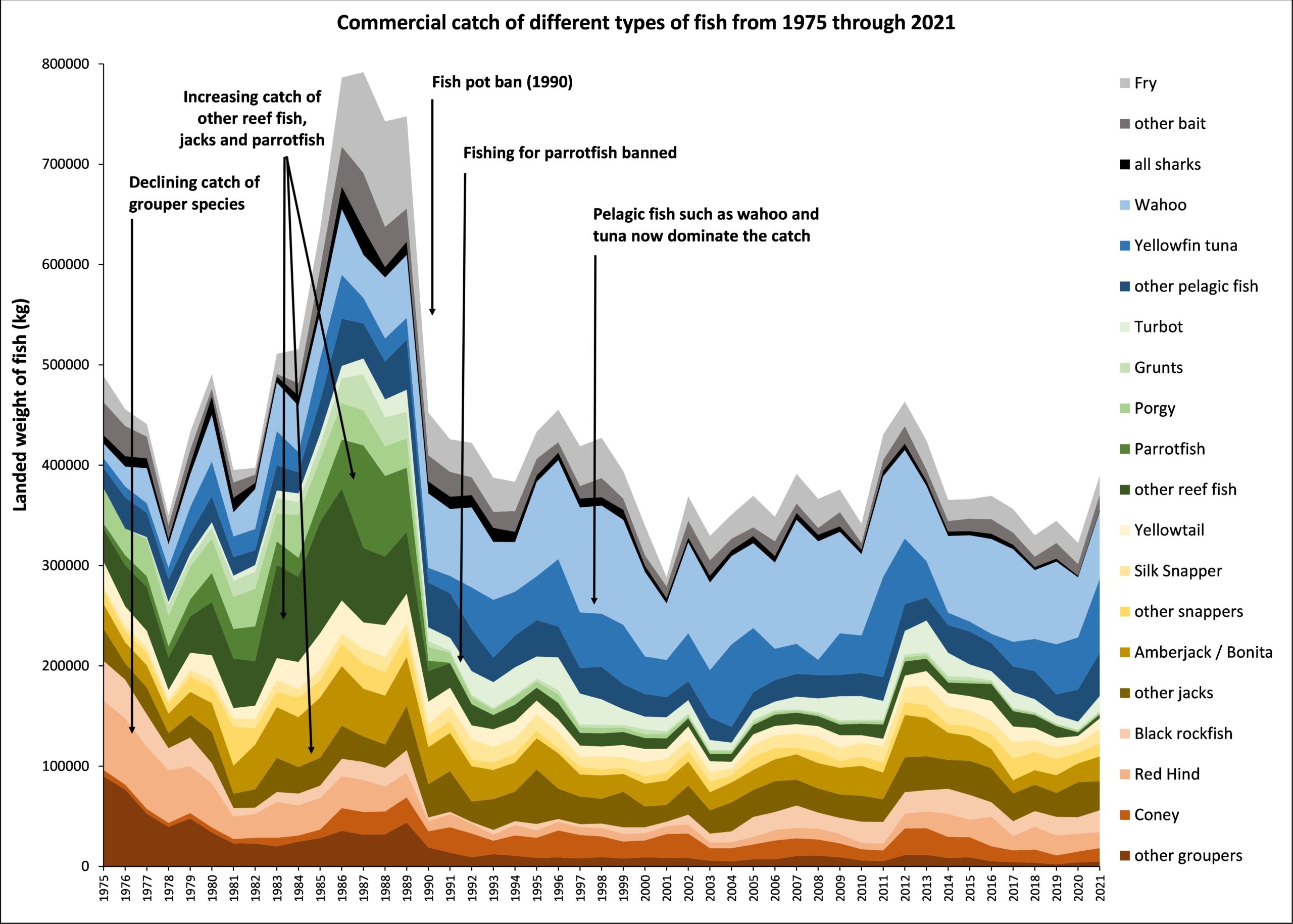

The graph on your screen shows reported commercial fisheries catches since 1975, and highlights how the use of fish pots, combined with increased demand from the booming tourism industry, led to overfishing during the 1970s and ’80s and subsequent changes in the commercial fishery. The thickness of each coloured band reflects the total weight of each species, or group of species, caught in a given year.

The graph shows the decline of groupers, followed by the rise and fall of various reef fish species in the catch, and then a transition to the current scenario where pelagic species like tunas and wahoo make up roughly half the catch by weight.

Today, the populations of many reef fish species are in a better state than they were when fish pots were banned in 1990. Catches of key species, such as Black grouper, Red hind and shallow water snappers, appear to be relatively stable over the past 10-15 years, which implies a sustainable level of catch. However, the amount of fish caught is still lower than in the past, and these species are rarely seen during independent surveys, suggesting that their numbers still need improvement. Independent surveys also show that some iconic species, like the Nassau grouper, are still showing no signs of recovery despite a ban on fishing for them that has been in place for nearly 30 years.

The species that are recovering are those whose spawning grounds were protected, have flexible nursery habitat requirements, and have also been managed through fisheries regulations such as daily catch limits and minimum size restrictions. The good news is that the recovery of these fish populations will be further assisted as the broader ecosystem and prey fish populations at the base of the food chain, caught in large numbers during the 1980s, continue to recover. Establishing MPAs can help with all of this.

The current Draft Marine Spatial Plan has focused on including Essential Fish Habitats, like nursery habitats and spawning sites, in the areas proposed as fully protected MPAs. This approach can further boost the recovery of these species and may help other species recover. Nine out of the ten areas proposed for full protection include Essential Fish Habitat. The three ‘highly protected’ areas covering the lobster reservoir and the two sizeable seasonal closure areas (the ‘hind grounds’) would continue allowing fishing within the bounds of the current regulations.

Additionally, they will prohibit certain activities, such as development, that would damage these essential habitats.

While MPAs do much to protect our ocean resources, they are not a silver bullet, and we must still proactively manage the fish outside these areas. With this in mind, the Bermuda Ocean Prosperity Programme (BOPP) has a dedicated sustainable fisheries work stream that supports the collection of additional data to help enhance our current fisheries management. The Red hind tagging study conducted last summer is one example, and we now have a better understanding of the status of this species.

It is important to note that the Draft Marine Spatial Plan also includes non-spatial goals and objectives, which address many of the fishers’ and conservationists’ concerns. Chief among them is requiring proper environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for developments, as well as improving monitoring and enforcement. Other goals focus on reducing marine pollution and restoring lost and damaged habitats.

While it is widely understood that MPAs can only reach their potential with these supporting measures, it is not necessary to wait for these measures to be in place before establishing a network of MPAs, as the various components of the Marine Spatial Plan can be implemented together.

While we are looking to expand Blue Economy opportunities in marine tourism, marine cultural heritage, ocean-based renewable energy and offshore fishing to create jobs and benefit all of Bermuda, placing additional demands on the marine environment without the insurance policy of MPAs is unwise. And so, the time to act is now.

Any content which is considered unsuitable, unlawful, or offensive, includes personal details, advertises or promotes products, services or websites, or repeats previous comments will be removed.

User comments posted on this website are solely the views and opinions of the comment writer and are not a representation of or reflection of the opinions of TNN or its staff.

TNN reserves the right to remove, edit or censor any comments.

TNN accepts no liability and will not be held accountable for the comments made by users.